Text rendering has been one of the more difficult areas in the Lightning 2.0 framework. Today, Lightning utilizes the browser’s Canvas 2D API to render text to a texture. It is then uploaded to the GPU where it is rendered to the screen just as if it were a PNG image. Unfortunately, the Canvas 2D text operations and texture uploading are single-threaded, CPU intensive, and consumes a large amount of memory on the GPU, which is scarce on embedded devices.

Here is list of the issues app developers have encountered with Canvas 2D text rendering in Lightning 2.0:

- Render performance

- When rendering lots of text, especially in lots of small Lightning elements, performance takes a big hit due to the CPU load required in rendering and uploading text textures to the GPU.

- There is also fairly intense work added on by Lightning in performing word wrapping and word breaks, which cannot be done with the browser native Canvas 2D APIs.

- Texture size dimension limits for rasterized text

- Individual textures on the GPU have a single dimension size limit, depending on the hardware used. On embedded devices this can be as low as 2048. Meaning neither the width or height of a single texture can be larger than 2048 pixels. This makes it difficult to render long scrolling blocks of text.

- Texture memory consumption

- Uploading rasterized text to the GPU consumes significant amounts of texture memory which is limited especially on embedded devices. The text texture is stored completely uncompressed.

- Scalability

- Scaling the text larger or significantly smaller results in jarring artifacts such as blurriness or aliasing. Re-rasterizing and uploading text texture on every change in scale (especially for animations) is way too CPU intensive to be viable.

- Various glitches

- There have been various notable glitches that have occurred with text rendering depending on the browser and device the Lightning app is running on.

Despite these drawbacks, using Canvas 2D is the simplest way to accurately render text using native browser calls.

In Lightning 3.0, we’re hard at work on a new option for text rendering that offloads the rasterization of text to the GPU. This method has significant CPU and texture memory savings, and even allows for the near infinite up/down scaling of text with virtually zero CPU involvement. But before we get into specifics, let’s understand what text rendering is, why it’s so hard, and how it is done today in browsers.

Text Rendering in a Nutshell

Isn’t text rendering just a matter of mapping binary characters one-to-one into symbols (officially called “glyphs” in the font world) and drawing those symbols one after the other on a screen? Unfortunately not. Even with a simple writing system like Latin, which this article is written in, there is more that needs to be considered when it comes to displaying text in a way that is pleasing to the human eye and as intended by the font’s designer. This includes a surprisingly vast array of adjustment features that may or may not be embedded into a font by the font designer as well as rules that apply to specific writing systems. This holds especially true for complex writing systems like Arabic which is not only written right-to-left but also involves many complex glyph substitutions and adjustments that occur in many complex contextual situations.

To get from a stream of Unicade Unicode encoded characters to pixels on a screen generally involves 4 major steps:

Font selection

This is how specific fonts are chosen from those available from the browser and/or operating system based on properties such as font family, style, weight, and size. The font property in CSS is one way these properties get specified before the selection process occurs. Fallback fonts are also chosen behind the scenes to fill in when the primary font is unable to render certain characters. For example, a font like Source Sans Pro does not contain Japanese characters but if you try to use them, the browser will automatically fall back to the best available font that does without you having to do anything. ちょうどこのような!Fonts on the web can come from the network (known as Web Fonts) or from those installed into the operating system (known as system fonts).

Bi-directionality resolution

Some writing systems, like Hebrew and Arabic, are displayed right-to-left even as their characters in memory remain oriented left-to-right. You may also have blocks of both left-to-right and right-to-left writing systems in the same line. There are many implicit rules and Unicode control characters that determine all of this. With a single stream of source characters, this stage determines which blocks are left-to-right vs right-to-left and re-sorts the character order to that in which they will visually appear on a screen. In some implementations, this can be lumped into the Shaping stage.

Shaping

This is generally regarded as the most complex area of text rendering. This stage is responsible for converting a stream of Unicode characters into a stream of specific font glyphs including how each glyph lines up with each other. This process takes into account the adjustment features programmed into the font for the given writing system.If you are curious, the documentation for HarfBuzz, the leading open source shaping solution (Fun fact: The WPE browser uses it), has an excellent overview of what shaping is. This more visual guide from Microsoft is great as well.

Rasterization

Finally once we know exactly what glyphs to render and where to render them, we move on to the rasterization step. Modern fonts typically store glyphs as mathematically defined vector paths (think SVG). These consist mainly of line segments and bezier curves. Vector path data is useless to screens and so they must first be rasterized, i.e. converted to a 2D array of pixels. Often this is done with drawing algorithms that run on the CPU. GPUs don’t natively understand vector path data either and so they require some specialized approaches in order to render them without the help of the CPU. We’ll talk about one of them below.

How Browsers Render Text

How do web browsers render text? It depends. The combination of the specific browser and operating system can make a big difference.

Operating systems such as Windows and MacOS provide proprietary text rendering APIs for all the stages listed above as part of their native application SDKs. It allows applications running on a platform the ability to tap into system fonts, share text rendering related memory resources and render text without each one having to embed their own text rendering libraries. It’s also often why text rendered across different applications on the same OS retain a consistent rendering quality. The way rasterization, for example, is done between different operating systems can vary a bit based on different approaches for anti-aliasing such as subpixel rendering.

Browsers typically tap into these operating system APIs for text rendering when both possible and practical. Some may use, for instance, HarfBuzz for shaping but the operating system APIs for rasterization. Some, like Chrome, may fallback to an open source alternative like FreeType if run on an older version of an operating system that does not support the latest text rendering features. Some browsers may opt to use open source solutions for everything, as is the case with WPE. Generally, all these steps happen on the CPU.

GPU Basics

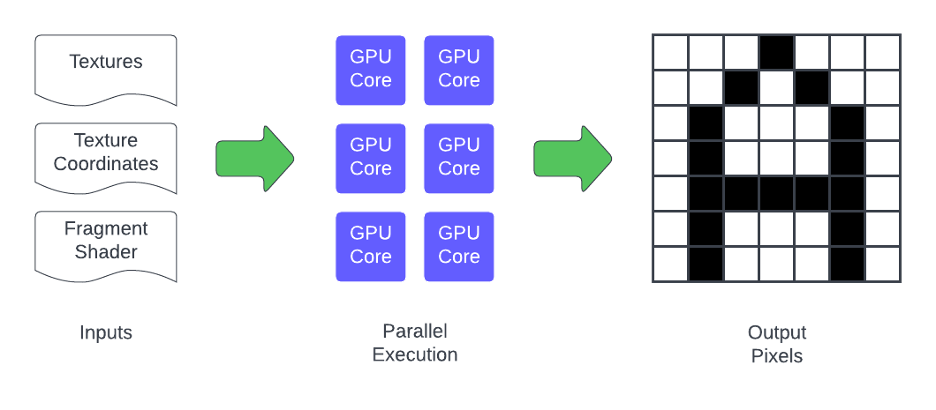

So how can we offload as much as possible to the GPU when rendering text? In case you aren’t aware, GPUs work mainly by running compiled shader programs over input data like polygon positions (i.e. vertices), textures and texture coordinates on all of its available cores. GPUs can have hundreds or even thousands of small cores, each one a much simpler version of a CPU core. These programs run independently and in parallel to calculate the final positions of vertices in a scene (vertex shaders) and compute the value of each pixel within each polygon (fragment shaders).

To understand the fragment shader, think of a grid of pixels that need to be rendered by a GPU. For each pixel, an instance of the fragment shader program will run on its own GPU core completely independent from the others until all the pixels have been calculated.

Vertex shaders work on a similar principle but deal with the vertex positions that f orm the geometry of the scene. Think of polygons in a 3D model. These run before the fragment shader. They are important but not as interesting in 2D applications, so we won’t go into them here. If you’d like to learn more about how GPUs and shaders work check out this presentation.

While we have a lot of cores to work with on the GPU, an overly complex shader can really chop down our frame rate. This means when it comes to rendering text on the GPU we need a method that can both independently and efficiently run for each pixel.

Signed Distance Field Text Rendering

In 2007 an engineer at Valve published a paper documenting a performant method of rendering sharp vector graphics that strongly leans on the GPU. It was originally used by Valve in its classic game Team Fortress 2. This method is known as rendering with “signed distance fields” (SDF). For Lightning 3.0, we’re adding the ability to render text using SDF.

Single-Channel Signed Distance Fields

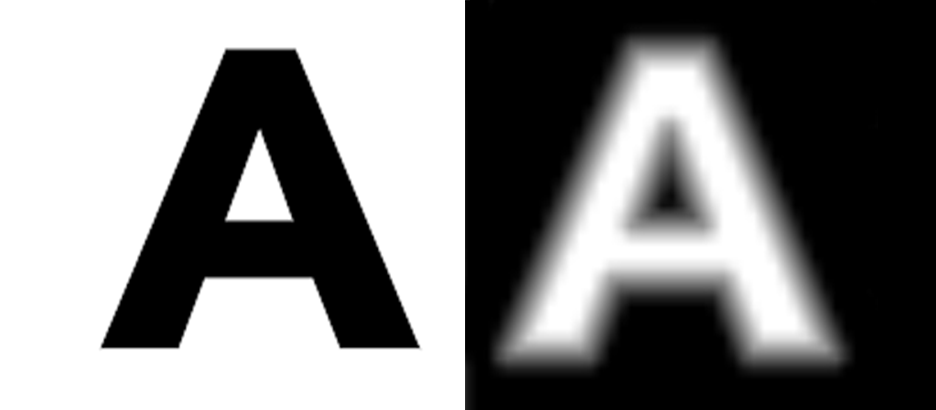

At its core, SDFs are a way of encoding vector shapes, like font glyphs, into a fairly low resolution texture that can be transformed into sharp rasterized shapes at virtually any resolution completely by the GPU. Let’s take a look at a capital letter “A” and it’s single-channel signed distance field representation:

“A” and it’s 36x34 SDF (enlarged)

You might first look at it and think it’s just a blurry beveled “A” but each pixel actually represents the shortest distance from the center of the pixel to an edge of the shape of “A” within a defined range. The monochrome (hence why it’s called “single-channel”) values 0 to 127 (black to darker gray) represent distances outside of the shape, and values from 128 to 255 (lighter gray to white) represent distances inside of the shape. Using simple math in a fragment shader with the native bilinear texture interpolation provided by the GPU that smoothly upscales the SDF texture we can render the shape at virtually any resolution and it will remain sharply defined! We can even add a little more math to the shader to get anti-aliasing (soft edges). The resolution of the texture just needs to be large enough to just clearly encode the details of the shape.

Single-Channel SDF Growing animation

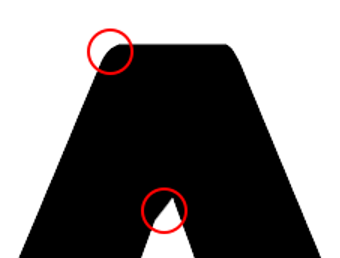

There is a particular downside to this approach that becomes more apparent the larger you scale the text. While the edges of the shape remain sharply defined at larger scales, you will notice certain details that have been blurred over by the SDF. All sharp corners are rounded out and certain details can be slightly warped. Let’s actually render that “A” using its SDF which only occupies 36x34 real pixels of the texture:

36x34 “A” SDF (enlarged) and what it renders into

If you look closely, all the sharp corners from the source “A” are rounded, and particularly the peak of the inner whitespace.

Blurred details of a single-channel SDF rendering

Depending on your precise design requirements and how large you are rendering text this may be barely noticeable and/or simply worth the efficiencies gained. But there are two ways to improve the situation if needed: increase the size of your source SDF or use what is called multi-channel signed distance fields (MSDF).

Multi-channel Signed Distance Fields (MSDF)

MSDFs improve render quality significantly by utilizing three channels (RGB), instead of one, to encode more information about a shape. There is a whole master’s thesis that goes into the details of how this method works. But here’s what an MSDF for the letter “A” looks like:

36x34 “A” MSDF (enlarged) and what it renders into

Like the single-channel SDF you basically have a blurry “A” but this time with a funky set of overlapping colors. By essentially just adding a function to calculate the median of the red, green and blue channels to our fragment shader code we now end up rendering a sharp A.

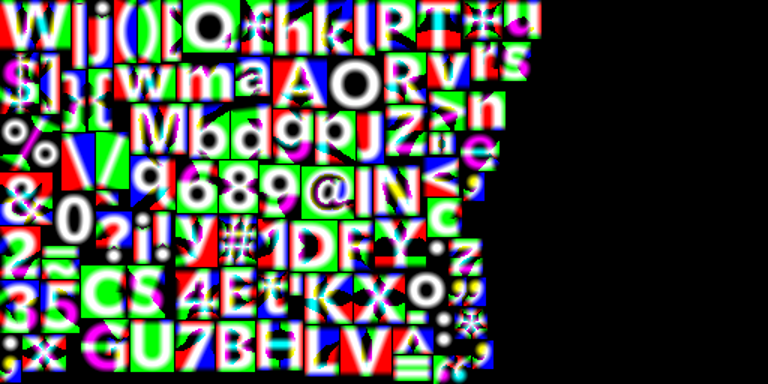

Why would you choose single-channel SDF over an MSDF? Well for one, the download size of the texture PNG will be smaller. The MSDF version of the atlas below is 106 KB while the single-channel version is 61 KB. But most importantly SDF textures consume ⅓ of the texture memory because they only use 8-bits per pixel.

This GitHub project is a great resource to learn more about MSDFs including the shader code involved in rendering them.

Rendering

In order to render text using one of these methods we need to, at build time, generate a texture map atlas of the SDFs for each glyph that we need in our application.

Single-Channel and Multi-Channel SDF Atlases

This can be done using an easy-to-use command line utility called msdf-bmfont-xml. It takes an input font file, a charset and some other properties and outputs a PNG glyph atlas like the ones above as well as a data file (JSON or XML) that contains the positions of each glyph in the atlas as well as other data that helps do some basic text shaping. In Lightning 3.0, we plan to offer this functionality built into our CLI tool.

This leads us to one of the biggest limitations to the SDF approach: only a limited subset of glyphs in a font can be included in the atlas. This is limited mainly by texture memory and the maximum size of textures. Thankfully this is generally NOT a big deal for writing systems like Latin with a relatively small glyph set. Trying to support a writing system like Chinese or Japanese will have its challenges but could be possible with a carefully chosen charset as well as potential techniques to progressively build an atlas on demand with the help of a server. Unfortunately the on-device generation of both single/multi-channel SDFs are likely too CPU intensive to consider for most embedded devices.

Shaping SDF Text

All of the above has focused specifically on rasterizing text with the GPU. As mentioned in the overview of text rendering, a major step in the process is text shaping. When using SDFs we can no longer rely on the text shaping provided by the browser/operating system. We are forced to roll our own. Thankfully the data generated along side the SDF atlas gives us enough information to do simple shaping for the simple writing systems like Latin. Shaping for more complex writing systems will require additional work. In Lightning 3.0, we are aiming to support the Latin script out of the box and provide a plugin surface for community support for complex scripts as they are needed.

Pros and Cons

Let’s see how SDF text rendering squares up against the same list of issues regarding Canvas2D text rendering that we presented at the beginning of the article.

- Render performance

- Rasterization is done completely on the GPU using a pre-loaded texture. CPU is largely needed for shaping the text.

- Word wrapping/word breaking can be done more efficiently since we have control of the shaping stage.

- Texture size dimension limits for rasterized text

- This does not apply at all for SDF rendered text. We can theoretically support infinite amounts of text (as long as there is enough CPU memory).

- Texture memory consumption

- Texture memory is significantly lower as only the SDF atlases need to be loaded onto the GPU.

- Scalability

- Text can scale up and down and remain crisp with virtually zero CPU involvement.

- Various glitches

- Many glitches involving Canvas2D rendered text involve the rasterization and then handoff of the rasterized canvas to the GPU. These types of glitches can be more confidently avoided.

As you can see SDFs can improve on all of those points significantly! But with these benefits come some trade-offs. Some have already been mentioned but lets summarize each one:

- Larger download

- Unfortunately the glyph shape data in stored SDF atlas textures and the accompanying JSON data can require more than double the number of bytes downloaded than a standard TTF font file.

Here is a comparison using the basic latin script font we used in the examples above:

- 66 kb TTF

- 61 kb SDF PNG + 73 kb JSON = 134 kb (2x TTF size)

- 106 kb MSDF PNG + 73 kb JSON = 179 kb (2.7x TTF size)

Atlas required for each font face

ach font face (i.e. regular, bold, and italic faces of the same font family) requires its own SDF atlas texture + JSON data generated at build time.

Atlas character set limit

This is mainly an issue for writing systems like Chinese or Japanese with an enormous glyph set due to texture memory and texture size dimension limits.

This could be made possible with a carefully chosen charset as well as potential techniques to progressively build an atlas on demand with the help from a server. More experimentation is necessary.

Unfortunately the on-device generation of both single/multi-channel SDFs are likely too CPU intensive to consider for most embedded devices.

Lack of fallback fonts

As mentioned, browser native text rendering has the ability to fallback to other fonts when certain characters are not available in the primary font. For SDFs, characters not found in the atlas will simply be skipped or be substituted by a stand-in glyph like a question mark “?”. Manual Text shaping

Since we don’t have the ability to reach into the browser’s native methods, text shaping must be done manually in JavaScript with data produced alongside the SDF atlas texture.

Text shaping is not guaranteed to support all of the adjustment features supported by a font. Text shaping may differ from what the browser would do.

As mentioned previously, we aim to provide a plugin surface in Lightning 3.0 to enable extensions for supporting more complex writing systems.

With that all said, we think the benefits of SDF text rendering outweigh the downsides of Canvas2D rendering for the vast majority of use cases involving writing systems with small glyph sets. But we do understand that SDFs will not be for everyone and we will continue to support Canvas2D rendering in Lightning 3.0.

Summary

The Lightning 3.0 framework is currently developing a new method for text rendering that offloads rasterization to the GPU. This is intended to save on CPU and texture memory, and allow for near-infinite scaling of text with minimal CPU involvement. The current method used in Lightning 2.x, which uses the browser's Canvas 2D API, is single-threaded and CPU-intensive, causing performance issues when rendering large amounts of text. The new method will address these issues, as well as the issue of texture size dimension limits for rasterized text. It will also solve the problem of texture memory consumption, and eliminate various glitches that have been observed with text rendering in different browsers and on different devices.

We hope you enjoyed learning more about text rendering and our efforts to improve it in Lightning 3.0. As we continue to develop Lightning 3 we will be sure to keep you updated on our progress and share our various findings. Keep an eye out for our next article on the topic of rendering and multithreading in Lightning 3.0.

The Lightning 3.0 is currently approaching it's first Alpha status. This will be an internal release that will be used to test the new features and APIs. The new Lightning 3 engine will be tested on various platforms and devices to ensure the best device compatibility. We will be sure to share more information about this release as it gets closer to the Beta release stage. The Beta release will be made available to the community for testing and feedback. If you are interested in learning more about Lightning 3.0, please go to our community forum at forum.lightningjs.io and post them there. We will be sure to respond to any questions you may have.

Thank you for reading and we hope you enjoyed this article.