Blits: Unlocking Performance in Your Big Screen Experience

Performance-obsessed technology for immediate rendering.

Blits is a brand new (well, 1 year old at the time of writing) JavaScript Application Development UI library for Lightning 3. Where Lightning 2 had a built-in application development syntax, Lightning 3 is split into two main building blocks: the renderer and Blits. This separation provides more flexibility and iterability between the two foundational pillars behind Lightning 3.

The Smart TV, game console, and set-top box space is a niche within a niche, and Lightning is the key player in that space. Most platforms come with a form of browser, usually far older than the one you’re using to read this. The one feature that ties them together is support for WebGL, which makes rendering stable across a wide array of devices, models, and years—dating from TVs running browsers built in 2014 to more recent versions.

But why is this a niche? Well, the performance of a Smart TV is somewhere between 10x to 100x slower than your average mobile device. This means that any performance gain, whether small or big, makes a major difference in running your TV experience on such a slow device. With that in mind, we created Lightning 3's Blits. A pure obsession with performance has resulted in an unparalleled application development framework with best-in-class efficiency.

The Lost Art of Performance

Although the trend of "going green" is slowly bringing the art of writing more performant code back into the spotlight, it's important to note the shift. The post-2000s and 2010s saw wild growth in endless resources, but these are now increasingly becoming a concern due to their carbon footprint. Efforts to reduce this are pushing tech to be more and more "green." However, in our niche market of highly resource constrained TV devices, the challenges are on a whole different level. This isn't just about going green, it's like we're back in the 80's, where you're working with a very constrained device and need to write a version of Mario Kart that runs consistently above 24 FPS.

The art of writing performant code for super-constrained devices slowly died in the late 90s. Before that, game systems like Atari, Nintendo, and early PC game engines were masterpieces of performance optimization, pushing the boundaries of what was possible. These efforts often led to crazy code patterns, many at the expense of readability (sorry, TypeScript). But with the rise of systems like the PlayStation 3, Xbox 360, and more powerful gaming PCs (RIP Voodoo Banshee with 3dfx Glide), the need for such intricate optimization began to fade.

We've had a few sessions where we revisited old 80s/90s game code just for the learnings. Sure, applying the same patterns in JavaScript isn’t always compatible. The language is just higher level than old C code, but some patterns still apply, and valuable lessons can be learned. By gaining a deeper understanding of the JIT tiers and how JavaScript engines interpret code, we were able to push performance for Lightning 3 Blits to its limits. This was no easy feat, and there’s always more to optimize, but it did lead to the fastest immediate rendering system available for JavaScript.

The JavaScript Compiler

Life in JavaScript is good, no worries about low-level tasks such as allocating/freeing memory, dealing with pointers, or thread locks. Easy peasy, right? Not if you want to achieve the absolute maximum performance. We’ve spent more time than we’re willing to admit benchmarking chunks of code. Every JIT (Just-In-Time) compiler has different strategies (V8 vs. JavaScriptCore), and many of our target devices use much older browsers, sometimes dating back over 10 years. Not only that, but Smart TVs almost always run in 32-bit userland, meaning the browser will also run in 32-bit. Meanwhile, in the desktop/mobile space, nearly all devices are 64-bit by now.

This matters because most modern browsers tend to focus on 64-bit-based JIT compilers, which means newer JIT optimizations are done exclusively for 64-bit systems. Not every project receives the same 32-bit backporting love. For example, JavaScriptCore’s FTL optimization tier has been available for 64-bit for several years, while the 32-bit version is still waiting to be finished. This might sound trivial, but it isn’t. It means your TV app experience isn’t going to get the same JavaScript compiler optimizations as you would on mobile or desktop.

As a result, we’re sometimes forced to lean into older patterns just to squeeze out every single grain of performance on older devices. That’s what makes the space Lightning operates in such an extreme niche compared to the broader desktop/mobile landscape. This is how we’re able to deliver the performance we promise with Lightning 3’s Blits application development framework.

Many, if not all, other JavaScript frameworks focus exclusively on desktop and mobile. Getting great performance on the latest 64-bit Chrome 128+ is fantastic, but it doesn’t translate into the same performance on a 10-year-old browser running on a constrained Smart TV with only half of the JIT performance tiers you’d normally expect.

Immediate Rendering

And then there’s the rendering aspect. Having a device with up to 100x less performance means you need to be smart about how to render animations and effects. DOM and CSS rendering aren’t always hardware-accelerated and have many issues with older browsers and limited feature support. Many browsers from 10 years ago don’t fully support newer CSS specs. If you’re reading this as a web developer, there’s no need to explain the struggles of CSS extensions and the pain of trying to animate even simple things on older browsers.

Now imagine doing more complex animations while still staying above the magic 24 FPS (frames per second) mark. In these cases, WebGL can achieve significantly better performance for more complex animations. Of course, there are limits: the GPU isn’t always very powerful, and too much JavaScript processing will shift the bottleneck to the CPU. However, having pixel-for-pixel control, direct access to the GPU, and our own rendering pipeline results in much higher efficiency than DOM-based rendering.

That’s the key difference. Immediate rendering means you render an entire scene from scratch every 16 ms (if rendering at 60 FPS). DOM rendering doesn’t work that way. Virtual DOM-based frameworks provide complete DOM updates and keep their "working" DOM in memory. This approach is quite slow and presents a big problem on resource-constrained devices. Newer frameworks use retained DOM updates, where the JavaScript framework "streams" the changed updates to the DOM tree.

This is very different from immediate rendering in WebGL. When the DOM tree is updated via streamed updates, the browser’s compositor marks a node as dirty, patches in the updated content, and flattens all the DOM layers back into one graphical layer. This process is called compositing, and the browser handles it for you.

With immediate rendering using WebGL, we’re talking directly to the GPU. This means we have to manage our own node tree, and as of now, the fastest way to do this is by providing complete scene updates. We re-render the entire frame from scratch every time because calculating the difference between frames is too CPU-intensive for our constrained devices.

It’s important to note that if a JavaScript framework is fast for DOM, this performance doesn't apply in any way to rendering in a immediate mode with WebGL. The DOM benefits are nonexistent, and therefore they’re not part of the performance equation. Instead, Lightning 3 precompiles, precomposes, and groups instructions specifically for immediate rendering scenarios. By tightly coupling the framework and the rendering, we achieve higher performance than if we were using a general-purpose JavaScript framework for a immediate rendering use case.

WebGL ≠ CSS

On top of that, styling, positioning, and effects are bespoke in JavaScript. Rendering in WebGL versus rendering in CSS is very different and cannot be applied 1:1. Features like specific shaders, render-to-texture, subtextures, sprites, and the variety of effects we can achieve in WebGL simply don’t exist in the DOM/CSS world. This means you either: a) provide a loosely specced mapping (whether best effort or very well documented), or b) create a custom, non-CSS specification to apply to DOM nodes to style, animate, or apply effects to your application.

As a result, Lightning 3 Blits has its own syntax for positioning, effects, and WebGL rendering features. Trying to reuse the existing CSS styling language for a WebGL use case doesn’t make sense and will only confuse the developer in the long run. What’s familiar might not work the way you’re used to, and avoiding ambiguity altogether is a much better strategy.

To make the framework familiar, similar patterns for how components are structured, how pages are built, and how to use templates are very much aligned with other XML-template languages such as Svelte and VueJS. This provides a familiar way of working for any web developer coming from a similar reactive web-based framework. Learning the key differences for WebGL-based immediate rendering is easy and intuitive, requiring little to no major adjustment for developers coming from CSS. In fact, in our experience, breaking away from CSS is a blessing, allowing us to leave a lot of technical debt behind.

Closing Thoughts

Lightning 3 is a high-performance, niche project designed for a very specific market: immediate WebGL rendering on highly resource-constrained devices. As such, we went to greater lengths than usual to ensure optimal performance on our target devices.

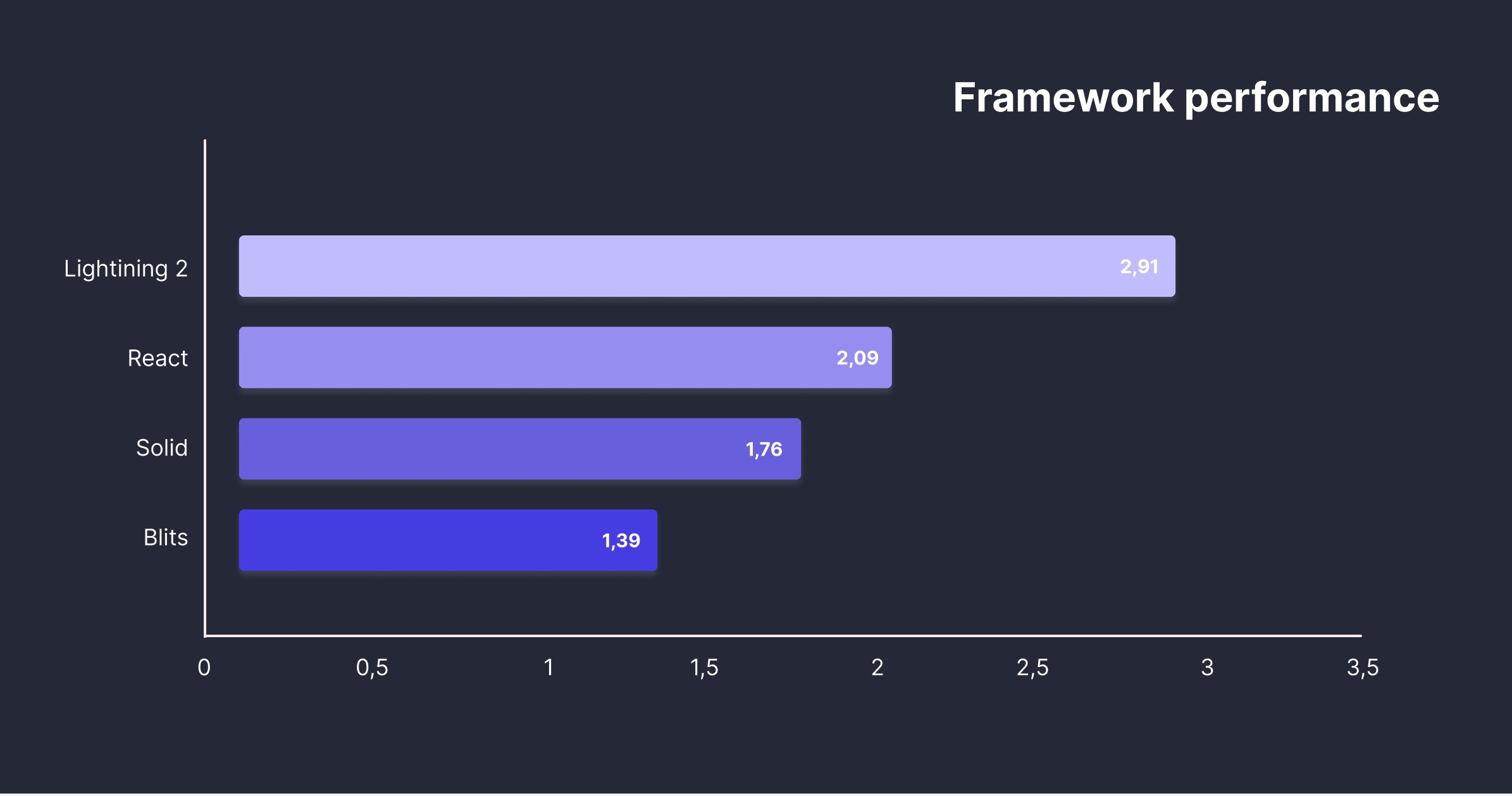

All this payed off in turning Lightning 3 Blits into the fastest framework for immediate rendering through WebGL. For more information please find the benchmarks here.

Specifically built for big-screen experiences on resource-constrained devices, Lightning 3 provides developers with a familiar, web-reactive framework to build their applications. This allows developers to benefit from a high-performance immediate rendering library without needing deep knowledge of low-level JIT optimizations.

Lightning 3 strikes a balance between a highly optimized, 80s/90s-inspired game engine and a modern-day reactive web programming syntax, delivering high-fidelity user experiences for resource-constrained big-screen devices.